RTS 3D

November 2021 - January 2022

The goal of this project was to develop a game for the Raspberry Pi, to prepare us for console development. I gained experience in hardware rendering and OpenGL. More advanced topics, such as instancing, animations and procedural textures were used. I learned my way around ImGui and the Bullet Physics library. The terrain and forests are procedurally generated, with a basic level editor to tweak the parameters as needed. The entire gamestate can be serialized to a compressed file, to be loaded in again at a later time.

Features

- Cross Platform: Creating support for Windows and Linux.

- OpenGL: My first experience with OpenGL and graphics programming.

- Seamless Texture Repetition: An technically complex technique used to reduce texture repetition.

- Serialization: Perfect serialization of all entity types.

- File compression: Algorithms & developing custom containers.

- Procedural-generation: Procedural levels and units.

Cross Platform

Working with the Raspberry Pi exclusively proved to be quite cumbersome, as everyday it took time to set up, the compilation time was incredibly slow, and it was tedious to record content. I decided to take an extra step beyond the requirements of this project and support a Windows build as well.

I used a few static libraries for input, graphics and physics, although I had never built a binary library myself. I learned how to build the necessary libraries on Windows.

My primitive approach to cross-platform support was to have two seperate projects in a .sln file. It worked, but it’s ofcourse tedious to maintain two seperate projects when adding/removing files. I learned the basics of cross-platform development, along with the knowledge of what to do different in future projects.

The final result was a game that I could develop on Windows, and only deploy on the Pi when needed. This sped up development tremendously, compilation times dropped from 5–10 minutes on the Pi to around 30 seconds on PC!

OpenGL

I was introduced to OpenGL this block and shader development.

The Raspberry has an integrated graphics card, and is incredibly slow. To get anything to render at an acceptable speed, I had to optimise the rendering pipeline by using instancing and frustum culling. I implemented simple Phong rendering, along with different settings to account for the difference in capabilities on the Pi vs PC.

|

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Highest texture resolution | Menu for graphical settings | Lowest texture resolution |

While animations are not strictly necesarry for a game like this, I wanted to learn how to render animated meshes. I followed this tutorial to learn about skeletal animation.

The tutorial’s content was helpful to get me started, but not very performance friendly and not const correct. There was a lot unnecessary copying of large amounts of data, they send a hundred matrices each frame representing the bone transform matrices even if there were only a few bones, and the shader itself had a lot of room for improvement. I’ve made a lot of changes from the original code, showing that my understanding goes further than knowing how to copy and paste existing code.

While dancing humanoids look fantastic, I ended up not using it in the final game. Instead, I use animations to renderer the various explosions in the game.

Seamless Texture Repetition

I achieved seamless tiling by sampling from multiple virtual texture variations, created through constant offsets, and smoothly blending between them. By using low-frequency procedural noise or lookup tables to drive the blending, this technique generates a filterable, non-repeating pattern with smooth transitions across regions.

|

|

|

|---|---|---|

| I’ve added a red triangle to allow the effect to be visible even on this small picture. It is obvious that it’s a repeating texture. | The procedural texture representing the index of the virtual variation of which to sample from. (Rounded to the nearest integer for this visualization) | By sampling different virtual textures we have hidden the tiling completely |

This article describes this technique in more detail.

Serialization

I am proud of my serialization system, especially since it seemed like the greatest challenge to me at the start of this block. The system can serialize arbirtrary data, including pointers and relations between different entities using entity IDs.

While it worked great, it required the user to write OnSave/OnLoad functions for each entity type to specify which members to serialize. This led to a lot of code repetition, and is something I hope to learn from for future projects.

File compression

While file compression is in no way a priority for a game like this, it’s something that I’ve wanted to take a stab at for a while.

I decided to use a huffman tree for this, a binary tree that takes individual bits and uses them to create the path from the root-node to the node with your information. This results in lossless compression, commonly recurring data that could be dozens of bytes long can now be represented with just a few bits.

I wanted to learn how to implement custom containers. I created a header-only dynamic_bitset container where you could easily manipulate individual bits. Unlike std::bitset, each boolean takes up exactly 1/8th of a byte, and unlike std::vector<bool>, I can access both the individual bits, aswell as the entire byte-buffer. I’ve learned how to make custom iterators for easier usage, for which I implemented custom reference types to reference the individual bits.

Once the dynamic_bitset was in place, I was able to create a templated header-only huffman-tree. The save file went from 7683KB to 2879KB, almost three times smaller!

Procedural generation

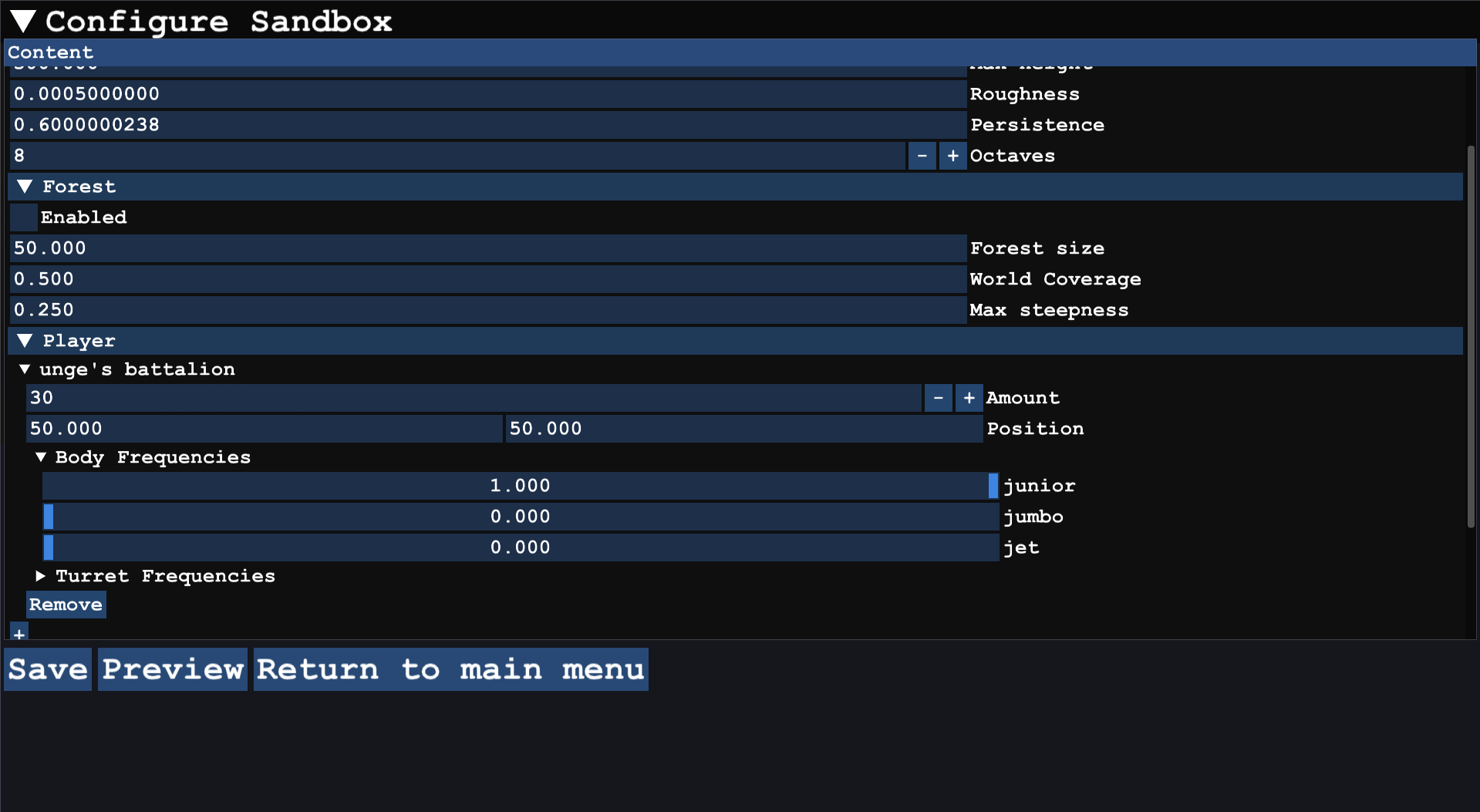

This game has a large focus on procedural generation. The terrain in the above images was procedurally generated, with a simple built-in editor for adjusting parameters.

For the procedural generation of units, I create a random combination of bodies and turrets. I have three bodies, a flying plane, a large tank, and a tiny tank. Each body contains properties such as max health, movement speed, and ‘nodes’ containing information about how turrets could be placed. The plane for example has three slots that are slightly angled downwards, and the large tank increases the size of whichever turret you assign to it. This creates slight variations in the available units:

I designed the turret’s and unit’s behavior to be completely independent of one another, which allows each unit to have a variable number of turrets.